Born in the Greco-Egyptian Alexandria of the early centuries, the Corpus Hermeticum travelled from scriptoria to printing presses, from alchemists’ workshops to humanist libraries. Translated, commented upon and transmitted, it offers less a closed doctrine than a path of knowledge: holding together reason and symbol, cosmology and ethics, study and self-transformation. One reads it amid the mingled scent of ink and sulphur, at the crossroads of the adept’s furnace and the copyist’s lamp; the voice of the theurgist meets the hand of the philosopher, and the “way of the mage” guards itself against illusion in order to seek inner order. Two millennia later, its promise remains clear: to understand the world in order to understand oneself.

Alexandrian Origins (2nd–3rd Centuries)

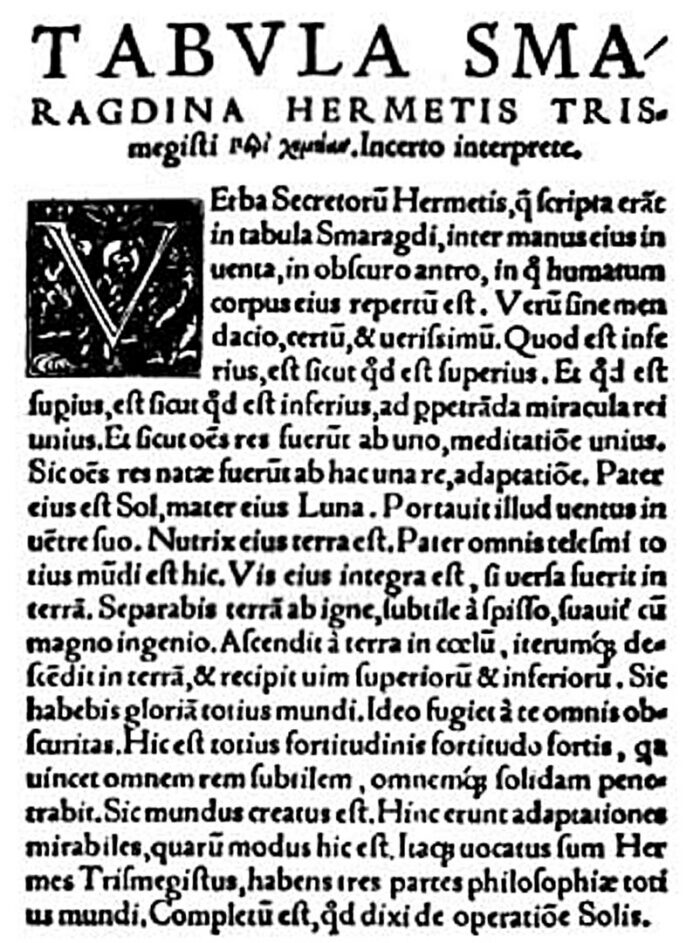

The Hermetic treatises, written in Greek and attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, take the form of sapiential dialogues. Their horizon is a crossroads where late Platonism, Stoicism, Egyptian piety and wisdom literature converge. They speak of the Noûs (Intellect that orders), of a living cosmos, and of an inner ascetic discipline that clarifies the soul. To know is not to accumulate: it is to undergo conversion. To avoid familiar confusions, let us recall that the Corpus Hermeticum (the Greek treatises) is not the Emerald Tablet (a later Arabic–Latin text), even though history has often intertwined their destinies in the alchemical imagination.

Oriented Knowledge, Not Doctrine

The Corpus Hermeticum is neither a systematic treatise nor a manual of practices. It consists of exhortations, dialogues and initiatory discourses that aim less at transmitting knowledge than at producing an inner displacement. The reader does not receive a doctrine to memorize, but an orientation of the intellect: learning to read the world as an ordered, living whole, traversed by correspondences. The fundamental principle is not the accumulation of notions, but the recognition of a profound accord between levels of reality: cosmos, soul and intellect partake of a single architecture.

The Law of Correspondences and the Order of the Living

This coherence rests upon an implicit law, omnipresent yet never formulated as an axiom: what is above responds to what is below, and what is understood in the mind finds its echo in matter. The world is not a chaos to dominate, but a text to decipher. Hence the importance accorded to the Noûs, the divine Intellect, not as an abstract faculty, but as a shared principle of intelligibility. To know, in Hermetic language, means to recognize order — and to align oneself with it. Such knowledge is inseparable from an ethic: it requires purification of vision, mastery of the passions, and the gradual rectification of the soul.

A Pedagogy of Inner Conversion

The Corpus thus proposes a genuine pedagogy of conversion. Hermetic discourse does not seek to persuade through demonstration, but to awaken through resonance. Images, myths, cosmologies and moral admonitions work together to produce a slow, often silent transformation. This is why these texts so deeply nourished alchemy, theurgy and symbolic medicine: they offer fewer recipes than criteria of rightness. They teach how to think before indicating what to think. In this sense, the Corpus Hermeticum acts as a matrix: a grammar for reading reality, rather than a fixed content.

Late Antiquity and the Latin Middle Ages: Continuity through the Asclepius

In the Latin West, only one related text circulated widely: the Asclepius, preserved in Latin, which carried Hermetic memory when access to Greek became scarce. Christian authors of late antiquity knew Hermes, sometimes with esteem, sometimes with reserve; yet most of the Greek corpus remained discreet until its humanist rediscovery. This slender thread nevertheless sufficed to irrigate the centuries: passing from monastic cells to astrologers’ cabinets, inspiring moralists, intriguing alchemists, and sustaining the idea of a wisdom that speaks at once of the world, the soul and God.

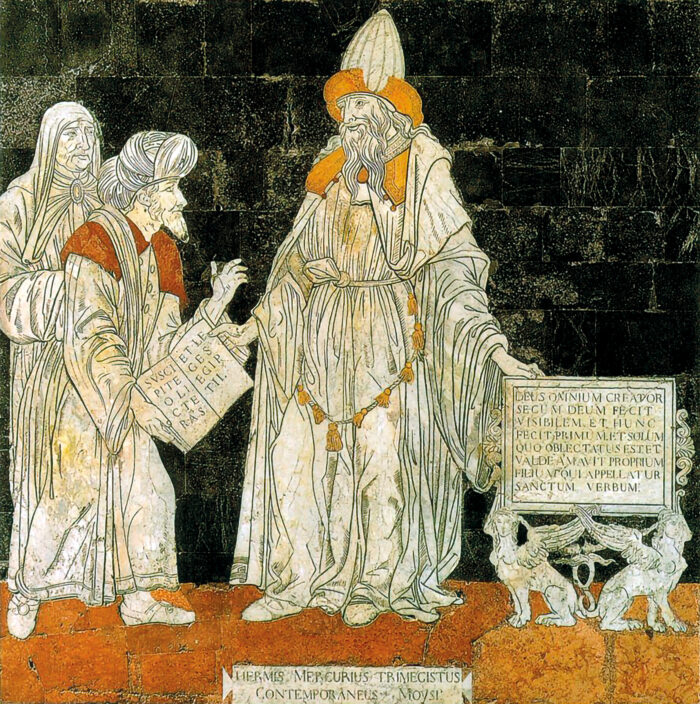

The Renaissance: A Rediscovery that Set Europe Ablaze (1460–1471)

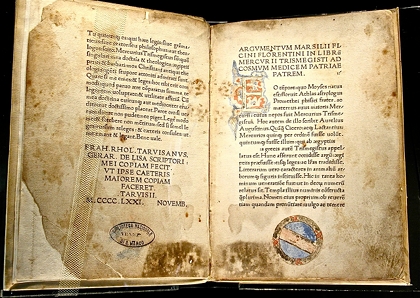

In 1460, a Greek manuscript reached Florence. Cosimo de’ Medici asked Marsilio Ficino to interrupt his work on Plato in order to translate urgently the “Pimander.” In 1463, the Latin translation was completed; in 1471, the first edition appeared. For the humanists, Hermes became a witness to the prisca theologia, an ancient wisdom believed to be universal. The impact was immediate: Pico della Mirandola, Agrippa, Paracelsus and Giordano Bruno drew from this source that nourished natural magic, theurgy, analogical medicine and a cosmology of correspondences. In workshops where engravings were made and in laboratories where substances were distilled, Hermes functioned as a symbol of concord among forms of knowledge: philosophy, medicine, astronomy and the liberal arts. Europe rediscovered itself by linking emerging science and contemplation, furnace and library, compass and prayer.

1614: The Critical Turning Point

In 1614, Isaac Casaubon demonstrated, through analysis of language and ideas, that the treatises belonged to late antiquity rather than to a pre-biblical age. The prisca theologia lost its chronological prestige; the authority of an “immemorial origin” faded. The episode was decisive, and it suffices in itself: it recontextualized the Corpus without nullifying it. Read without the legend of primordial antiquity, the treatises gained historical precision while losing mythic aura — and their voice remained, now more sober and more grounded.

19th–21st Centuries: Patient Philology, Renewed Horizons

The modern period brought order: critical editions, scholarly translations and sustained commentary. A.-J. Festugière illuminated Hermeticism as a philosophical religion of late antiquity; contemporary scholarship (Mahé, Yates and others) refined its contexts, genres and influences. One no longer reads a fixed block, but a constellation of converging treatises: exhortations, homilies and dialogues in which the discipline of language accords with the discipline of the soul. From the alchemist’s workshop to the theurgist’s meditations, from the philologist’s study to the Paracelsian physician’s cabinet, Hermes continues to irrigate practices quietly — not through recipes, but through a grammar of unity, in which each thing corresponds and answers to another.

Why This Corpus Still Speaks to Us

What captivated Ficino — and what still resonates today — is not the illusion of a fabulous antiquity, but the staging of a knowledge that transforms. No recipes, no effects: an inner method. To see order in the world is to order one’s life. To reconcile rational inquiry and symbolic language; to accept that the language of images and that of concepts may dwell together. For the alchemist, this is called transmutation; for the theurgist, illumination; for the non-initiated reader, simply unifying what one knows with what one lives. This promise explains the longevity of the Corpus: it helps hold together what our age too often separates.

Three Titles Often Confused

Corpus Hermeticum : a collection of Greek treatises (sapiential dialogues) from late antiquity.

Asclepius : a related Latin text widely circulated in the medieval West.

Emerald Tablet : a brief Arabic–Latin text, not included in the Corpus, which became emblematic of alchemy.

Key Milestones

2nd–3rd centuries: composition in Greek (Alexandria).

4th–5th centuries: references in Lactantius and Augustine; diffusion of the Asclepius

1460–1463: Latin translation by Marsilio Ficino.

1471: first printed edition.

1614: late dating established by Casaubon.

20th–21st centuries: critical editions, commentaries and historical reassessments.

Conclusion

A text that survives changes of era does not impose itself by prestige, but by the service it renders: it opens a passage. The Corpus Hermeticum endures because it recalls a simple and demanding truth: to know is to undergo conversion; to illuminate the intellect is already to illuminate life. Far from being a frozen monument, it remains a grammar of breathing for the mind — a thread of light that mages, alchemists and theurgists have grasped in turn to link matter and meaning. In the spirit of our Rite, it was an inexhaustible source of inspiration for Robert Ambelain (1907–1997) as he rewrote, during the second half of the twentieth century, the texts that structure our present practice. Without revealing anything of internal workings, it suffices to say this: from Alexandria to the modern world, Hermes continues to invite unity — that of symbol and reason, study and life.

To go further

- André-Jean Festugière, La Révélation d’Hermès Trismégiste (Les Belles Lettres / Vrin).

- Hermès Trismégiste, Corpus Hermeticum (Les Belles Lettres).

- Frances A. Yates, Giordano Bruno et la tradition hermétique (Dervy).

- Jean-Pierre Mahé, Hermès en Haute-Égypte (Presses de l’Université Laval).

The above references are provided for informational and cultural purposes only. There is no commercial relationship with the authors, publishers, or platforms mentioned; these links are not advertisements, but rather further reading intended to provide more in-depth information on the subject matter.

Where possible, the images used to illustrate these articles are systematically accompanied by a reference to their source and credits. Where no source is indicated, this is because the information was not available. These images are used solely for illustrative purposes, in a non-profit context, without any commercial intent or appropriation of the work.